I have a lot of favorite artists, but one historical painter that I really appreciate is Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

He lived from 1780-1867 in France (as if the name didn't tip you off), and he was a member of the "Neo-classical" style, meaning that he was part of the movement that looked back to the Classical era of art - Ancient Greece and Rome, and the Renaissance (which in turn also looked back to the Classical era) - for inspiration.

It's a bit of an oversimplification to say that Western artistic tastes throughout time basically fall into two camps - Classical/Photo-realistic and Emotive/Romantic/Non-Photorealistic - but that's often how intro art history classes frame it.

Classical styles are ones that focus on how things look - scientifically, mathematically, realistically. They often coincide with a greater societal interest in math and science, or are influenced by new technologies and empirical observations. These include advances in perspective that the Renaissance saw, where artists studied architecture and used mathematical formulas to lay out the composition of their paintings to achieve a "perfect" ratio. These also include advances in biology, where artists studied models from life - or even used cadavers - and practiced getting anatomy drawn correctly.

The more emotional styles focus on a different reality. You could argue they're still realistic - but it's just that they're looking at the realism of feeling and emotion. Instead of trying to mimic what the eye sees, they try to mimic what the heart feels. This includes completely abstract styles that have come about in modern art (art since the mid-1800s) and were especially prevalent around the World Wars. But it also includes before that styles that favored dark, moody palettes that added drama and tone to a painting, or paintings that used asymmetrical and dynamic, diagonal compositions to capture a mood.

Indeed, for awhile a pattern seemed to emerge wherein artists (or perhaps more accurately, the critics and salons that publicly supported art) swung back and forth between these two styles.

Ancient Greece & Rome (Classical art, concerned with realistic depictions of the human form and specific architecture ratios) -> Medieval Art (Emotional art, not concerned with realistic depictions of the human form - just look at any Gothic Virgin Mary & Baby Jesus painting) -> Renaissance Art (again concerned with math, science, and true-to-life realism) -> Baroque Art (which did not disregard the strides made by Renaissance Art and were often very photo-realistic, but at the same time focused also on dark subject matter, dynamic compositions, lots of movement, and often dark backgrounds) -> Neo-Classical Art (so-called because it purposefully swung the pendulum back to looking at Ancient Greece & Rome) -> Romantic Art (which again swung back to look at dark, often disturbing subject matter, wild nature, Gothic architecture, etc.) -> Realism (which again tried to copy life as it was seen) -> Impressionism (considered the beginning of Modern Art)

Until modern art, the "accepted" style just sort of went back and forth between these extremes. That is not to say that artists followed the accepted style, or that artists didn't use elements of both styles. Just that, in general, if you look at these broad eras, there seems to be a shift of focus that happened every century or so.

Impressionism, by the way, is considered the beginning of Modern Art because it was a clear melding of these two camps. These artists were trying to get into the details of how the eye perceives the way it does, and use this scientific knowledge of the human eye to their advantage to make dynamic paintings. And so you have Monet, who used dabs of color next to each other that weren't softly blended together - because he understood the science that our eyes would do that blending for us, and interpret the painting appropriately. To the extreme, this led to Pointilism:

It uses scientific theory to create what would have once been considered a more emotional way of painting - with visible brushstrokes and dabs of paint. And yet, it's also kind of stiff, and not really emotional at all. For a group of people relaxing on a Sunday Afternoon, there are a lot of straight backs (which are repeated vertical lines throughout the canvas).

But to get back to Ingres...

Ingres lived before Impressionism and the Modern age. He lived during the Neo-Classical and Romantic eras, and though he is often classified as a Neo-Classical painter, there are elements about his work that are often strange - almost Romantic in style.

He considered himself Neo-Classical, and aligned himself with other Neo-Classical painters like Nicolas Poussin and Jacque-Louis David. As his Wikipedia page says -

A man profoundly respectful of the past, he assumed the role of a guardian of academic orthodoxy against the ascendant Romantic style represented by his nemesis, Eugene Delacroix... He once explained... "I am thus a conservator of good doctrine, and not an innovator." Nevertheless, modern opinion has tended to regard Ingres and the other Neoclassicists of his era as embodying the Romantic spirit of his time, while his expressive distortions of form and space make him an important precursor to modern art.

He detested the Romantic style. His brushworks were very clean and controlled. His subjects were very orthodox. He was even employed as a state painter for Napoleon (meaning that the government recognized his work as being the appropriate style - Neo-classical). And yet - within his seemingly "perfect" paintings, which at first glance appear perfectly proportioned, exquisitely detailed, and realistically rendered, there are, at second glance, obvious imperfections.

Look at her arms. One is up on the seat she's leaning against, and seems correctly proportioned. But the other arm, the right one, extends far further down than it should be able. It is much longer than her left arm appears to be. Furthermore, her billowing shawl conceals her elbow, so we cannot see where it is bent. It is almost as if she has no elbow on the right side at all, and her arm is an elongated, rubbery extension - a quirk much more akin to the Romantic style of painting.

Take this next painting - La Grand Odalisque. Her arms are also seemingly elongated - and her legs stick out weirdly from her hips. Where exactly does her left leg attach to her?

His style is reminiscent of the Mannerist style of painting - the transition period between Renaissance and Baroque art a couple centuries prior, which also showcased elongated limbs - often coupled with dramatic, crowded compositions and strange color choices.

Ingres was on a quest to find the perfect human form. He worked with models who were beautiful - and yet he adjusted their proportions to dramatic effect in his work, in an attempt to make them more beautiful. (Perhaps not too different from the way magazines Photoshop models today.)

But here's what I really like about his work - the adjustments he made to his models made them less perfect. He was trying to get a perfect beauty, and to tweak his paintings to get perfect compositions - but to do so he gave the people who populated them imperfections. One arm that is longer than another. One leg which is shorter than another. If we saw such people walking down the street, their imperfections would jump out at us. But in Ingres's paintings, they're beautiful. He purposefully gave them what many of us would consider "imperfections" or "flaws" - in order to make them more beautiful.

That's a pretty powerful message. I'm not sure if it is exactly what he intended, but in college when I was learning about Ingres, I got really excited about that idea. That our flaws not only make us who we are but perhaps make us better. That our imperfections might counter-intuitively but truthfully make us more perfect. It's the irony, the relief, the beauty of perfect imperfections.

And that is why I was drawn to Ingres's work - because I feel that it embodies a message that is all too easy for me (and many of us) to forget. We don't have to fear failure, or try to hide our flaws. We should embrace that what makes us unique, and use our unique abilities to be our best selves. We can be imperfect and perfect. We can be flawed and beautiful. It's something we should all try to remember more.

|

| Ingres - Self Portrait at age 24 (1804) |

He lived from 1780-1867 in France (as if the name didn't tip you off), and he was a member of the "Neo-classical" style, meaning that he was part of the movement that looked back to the Classical era of art - Ancient Greece and Rome, and the Renaissance (which in turn also looked back to the Classical era) - for inspiration.

It's a bit of an oversimplification to say that Western artistic tastes throughout time basically fall into two camps - Classical/Photo-realistic and Emotive/Romantic/Non-Photorealistic - but that's often how intro art history classes frame it.

Classical styles are ones that focus on how things look - scientifically, mathematically, realistically. They often coincide with a greater societal interest in math and science, or are influenced by new technologies and empirical observations. These include advances in perspective that the Renaissance saw, where artists studied architecture and used mathematical formulas to lay out the composition of their paintings to achieve a "perfect" ratio. These also include advances in biology, where artists studied models from life - or even used cadavers - and practiced getting anatomy drawn correctly.

The more emotional styles focus on a different reality. You could argue they're still realistic - but it's just that they're looking at the realism of feeling and emotion. Instead of trying to mimic what the eye sees, they try to mimic what the heart feels. This includes completely abstract styles that have come about in modern art (art since the mid-1800s) and were especially prevalent around the World Wars. But it also includes before that styles that favored dark, moody palettes that added drama and tone to a painting, or paintings that used asymmetrical and dynamic, diagonal compositions to capture a mood.

Indeed, for awhile a pattern seemed to emerge wherein artists (or perhaps more accurately, the critics and salons that publicly supported art) swung back and forth between these two styles.

Ancient Greece & Rome (Classical art, concerned with realistic depictions of the human form and specific architecture ratios) -> Medieval Art (Emotional art, not concerned with realistic depictions of the human form - just look at any Gothic Virgin Mary & Baby Jesus painting) -> Renaissance Art (again concerned with math, science, and true-to-life realism) -> Baroque Art (which did not disregard the strides made by Renaissance Art and were often very photo-realistic, but at the same time focused also on dark subject matter, dynamic compositions, lots of movement, and often dark backgrounds) -> Neo-Classical Art (so-called because it purposefully swung the pendulum back to looking at Ancient Greece & Rome) -> Romantic Art (which again swung back to look at dark, often disturbing subject matter, wild nature, Gothic architecture, etc.) -> Realism (which again tried to copy life as it was seen) -> Impressionism (considered the beginning of Modern Art)

Until modern art, the "accepted" style just sort of went back and forth between these extremes. That is not to say that artists followed the accepted style, or that artists didn't use elements of both styles. Just that, in general, if you look at these broad eras, there seems to be a shift of focus that happened every century or so.

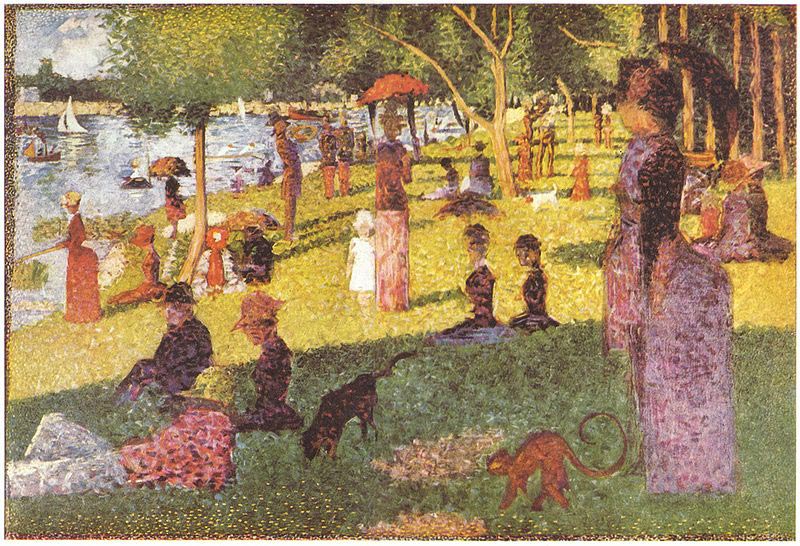

Impressionism, by the way, is considered the beginning of Modern Art because it was a clear melding of these two camps. These artists were trying to get into the details of how the eye perceives the way it does, and use this scientific knowledge of the human eye to their advantage to make dynamic paintings. And so you have Monet, who used dabs of color next to each other that weren't softly blended together - because he understood the science that our eyes would do that blending for us, and interpret the painting appropriately. To the extreme, this led to Pointilism:

|

| Georges Seurat - A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86) |

It uses scientific theory to create what would have once been considered a more emotional way of painting - with visible brushstrokes and dabs of paint. And yet, it's also kind of stiff, and not really emotional at all. For a group of people relaxing on a Sunday Afternoon, there are a lot of straight backs (which are repeated vertical lines throughout the canvas).

But to get back to Ingres...

Ingres lived before Impressionism and the Modern age. He lived during the Neo-Classical and Romantic eras, and though he is often classified as a Neo-Classical painter, there are elements about his work that are often strange - almost Romantic in style.

He considered himself Neo-Classical, and aligned himself with other Neo-Classical painters like Nicolas Poussin and Jacque-Louis David. As his Wikipedia page says -

A man profoundly respectful of the past, he assumed the role of a guardian of academic orthodoxy against the ascendant Romantic style represented by his nemesis, Eugene Delacroix... He once explained... "I am thus a conservator of good doctrine, and not an innovator." Nevertheless, modern opinion has tended to regard Ingres and the other Neoclassicists of his era as embodying the Romantic spirit of his time, while his expressive distortions of form and space make him an important precursor to modern art.

He detested the Romantic style. His brushworks were very clean and controlled. His subjects were very orthodox. He was even employed as a state painter for Napoleon (meaning that the government recognized his work as being the appropriate style - Neo-classical). And yet - within his seemingly "perfect" paintings, which at first glance appear perfectly proportioned, exquisitely detailed, and realistically rendered, there are, at second glance, obvious imperfections.

|

| Ingres - Madame Riviere, 1806 |

Look at her arms. One is up on the seat she's leaning against, and seems correctly proportioned. But the other arm, the right one, extends far further down than it should be able. It is much longer than her left arm appears to be. Furthermore, her billowing shawl conceals her elbow, so we cannot see where it is bent. It is almost as if she has no elbow on the right side at all, and her arm is an elongated, rubbery extension - a quirk much more akin to the Romantic style of painting.

|

| Ingres - La Grande Odalisque, 1814 |

Take this next painting - La Grand Odalisque. Her arms are also seemingly elongated - and her legs stick out weirdly from her hips. Where exactly does her left leg attach to her?

His style is reminiscent of the Mannerist style of painting - the transition period between Renaissance and Baroque art a couple centuries prior, which also showcased elongated limbs - often coupled with dramatic, crowded compositions and strange color choices.

| El Greco - The Burial of Count Orgaz (Mannerist style painting, 1586) |

Ingres was on a quest to find the perfect human form. He worked with models who were beautiful - and yet he adjusted their proportions to dramatic effect in his work, in an attempt to make them more beautiful. (Perhaps not too different from the way magazines Photoshop models today.)

But here's what I really like about his work - the adjustments he made to his models made them less perfect. He was trying to get a perfect beauty, and to tweak his paintings to get perfect compositions - but to do so he gave the people who populated them imperfections. One arm that is longer than another. One leg which is shorter than another. If we saw such people walking down the street, their imperfections would jump out at us. But in Ingres's paintings, they're beautiful. He purposefully gave them what many of us would consider "imperfections" or "flaws" - in order to make them more beautiful.

That's a pretty powerful message. I'm not sure if it is exactly what he intended, but in college when I was learning about Ingres, I got really excited about that idea. That our flaws not only make us who we are but perhaps make us better. That our imperfections might counter-intuitively but truthfully make us more perfect. It's the irony, the relief, the beauty of perfect imperfections.

And that is why I was drawn to Ingres's work - because I feel that it embodies a message that is all too easy for me (and many of us) to forget. We don't have to fear failure, or try to hide our flaws. We should embrace that what makes us unique, and use our unique abilities to be our best selves. We can be imperfect and perfect. We can be flawed and beautiful. It's something we should all try to remember more.

No comments:

Post a Comment